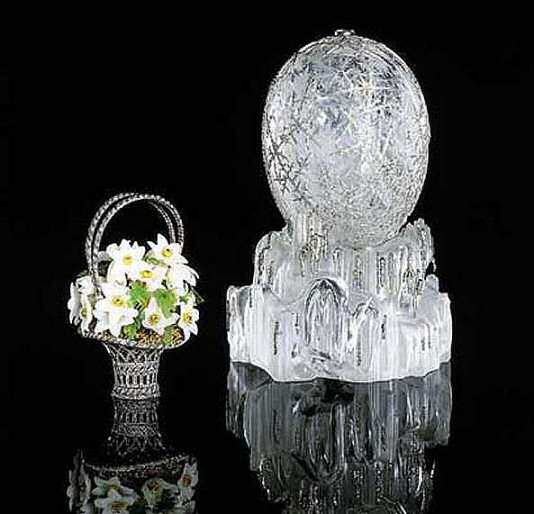

1913 Winter Egg

Gift Nicholas

II to Maria Feodorovna

Made in

Saint Petersburg

Owner: Private

Collection Qatar

Height: 10,2 cm

The 1913 Winter Egg is made of rock crystal, platinum, rose-cut diamonds, brilliant diamonds and moonstone.The miniature basket is made of platinum, gold, white quartz, nephrite and demantoid green garnets.

The Egg is set on a rock crystal base formed as a block of melting ice, applied with platinum-mounted rose-cut diamond rivulets. The hinged, rock-crystal egg is detachable and is held vertically above by a pin, with rose-diamond set platinum borders, graduated around the hinge and enclosing in the top a cabochon moonstone painted on the reverse with the date 1913, the thinly carved transparent body of the Egg finely engraved on the interior to simulate ice crystals, the outside further engraved and applied in carved channels with similar rose-diamond set platinum motifs, opening vertically.

The surprise is a platinum double-handled trellis work basket, set with rose-diamonds and full of wood anemones, suspended from a platinum hook, each flower realistically carved from a single piece of white quartz with gold wire stem and stamens, the center set with a demantoid garnet, some carved half open or in a bud, the leaves delicately carved in nephrite, emerging from a bed of gold moss, the base of the basket engraved in Roman letters "Fabergé 1913".

The Winter Egg is made of finely carved, transparent rock crystal with delicate engravings on the interior simulating ice crystals. The exterior is further engraved and applied with similar platinum-mounted rose-diamond motifs. The egg contains a cabochon moonstone painted with the date 1913 on top and rests on a detachable rock-crystal base formed as a melting block of ice and applied with platinum-mounted rose-diamond rivulets. The surprise consists of a platinum double-handed trellis work basket set with rose-diamonds and filled with spring flowers that emerge from a bed of golden moss. Each flower, realistically carved from a single piece of white quartz, is fashioned with gold wire stem and stamens, nephrite leaves and green garnet centers. Both the egg and the base of the basket are dated 1913, an important year marking the tri centenary of the Romanov Dynasty, celebrated lavishly throughout Imperial Russia.

The history of the Winter Egg is one of the best documented of all Imperial Easter Eggs. Not only do we know the workmaster, the designer and even perhaps the stone carver, but we also know the egg's cost in 1913. The original Fabergé bill in the Russian State Archives records the purchase of the Winter Egg by the Tsar for 24,600 rubles, the highest price ever paid for a Imperial Easter Egg. The bill also details the composition of the Egg: the body set with 1,300 rose-diamonds, the borders with 360 brilliants, and the small basket with 1,378 rose-diamonds.

The flower compositions created by Fabergé, such as the basket of spring flowers in the Winter Egg, stand out among some of the most technically demanding works produced by the firm. Spring flowers were a particularly celebrated theme among the Russian elite, as a symbol of happiness and renewed hope after long and pitiless winters.

Background information

The Winter theme was introduced by Fabergé's designer Alma Pihl. When asked to quickly complete a 40 piece commission for the magnate Dr. Emmanuel Nobel, Pihl drew inspiration from the sunlight sparkling through the draughty workshop's windows. This sight reminded her of an enchanted garden of frost flowers, and thus resulted in many frost-flower bracelets, pendants and brooches, set in platinum-silver and richly-set with the tiniest rose-cut diamonds. She was then asked to design the Imperial Easter Egg for the following year, The Winter Egg.

At 20 Alma joined the St Petersburg workshop of her uncle, Albert Holmström, then Fabergé's head jeweler. As an apprentice draughtsman, she made accurate full-scale sketches of each object constructed, with details of the stones used and labor costs. During rare moments of leisure, she tried her hand at designing herself. Uncle Albert saw her efforts and showed them to the sales department, who declared them excellent. Thus began Alma's career as an assistant designer. Early in January 1912, an urgent commission for forty small brooches came in from an important client, the magnate Dr Emanuel Nobel. The brooches (which were perhaps destined to be given to foreign clients' wives at his business dinners) had to be of a completely new design, but the materials should be inexpensive so they could not be interpreted as bribes.

This was Alma's great chance. Hoarfrost covered the draughty workshop's windows and when the sun shone, it dazzled like an enchanted garden of frost flowers. The sight inspired her - and the brooches were so successful Dr Nobel made many similar commissions. All winter she designed frost-flower bracelets, pendants and more brooches, in platinum-silver richly set with the tiniest rose-cut diamonds. Then she was asked to design an Imperial Easter egg for the following year - the Winter Egg. In far northern Europe, Easter falls when the snows are melting, the light is returning, and the sun is often shining brightly in a clear blue sky.

The Winter Egg brilliantly depicts this time of the year. In March, minute rivulets of water trickle down Nature's ice sculptures, glistening like diamonds in the sun. Siberian rock crystal was the perfect material to depict the ice, and in April a magic carpet of white wood anemones appears in the woods. Alma chose a small platinum basket of these heralds of spring, carved in white quartz, as the surprise inside the egg. We have no written evidence of the Dowager Empress's reaction, but Alma was asked to design Tsarina Alexandra's Easter egg the following year (the Mosaic Egg, now in the collection of Queen Elizabeth II).

Alma's career at Fabergé ended with the Russian Revolution. After years of hardship, she and her husband Nikolai Klee finally obtained permission to leave Petrograd (as St Petersburg had become) for Finland in 1921. A petite lady with very sharp eyes, always friendly, she taught art in a provincial secondary school from 1928 to 1951. Her pupils have fond memories of their inspiring teacher but they knew nothing about her remarkable background. When instructing, she wielded her pencil like a magic wand, brilliantly adding a line here or a dash there, miraculously transforming their drawings into works of art.

The Winter Egg was in 1927 one of the nine Imperial Eggs sold by the Antikvariat to Emanuel snowman of Wartski, London. 1934 sold to lord Alington, London. 1935 Owner anonym. 1848 owned by the late Sir Bernard Eckstein, UK. 1949 sold by Sotheby's London to a Bryan Ledbrook, UK. Disappeared around 1975 after Mr. Ledbrook died. 1994 located in a London safe. November 1994 sold by Christie's Geneva on behalf of a trust to a telephone bidder, acting for a US buyer. 2002 sold by Christie's New York to a bidder from Qatar.

Update Januari 15, 2021, while doing some research, I realised that the Winter Egg is the only Egg that was sold three times at auction. Several Eggs sold twice, but Winter Egg on top with thrice!

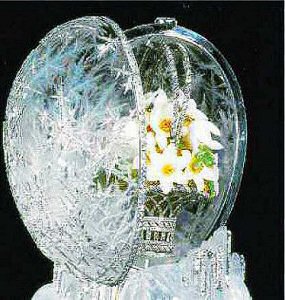

Image below captured from the auction 2002 video, showing the opened Egg without the base. AP video.