1892 Diamond Trellis Egg

Gift Alexander

III to Maria Feodorovna

Made in Saint Petersburg

Owner Egg: McFerrin Collection, Houston, USA

Height: 10,8 cm

Owner Surprise: Royal Collection HM Queen Elisabeth II, London, UK

Height: 6.0 x 5.5 x 3.4 cm

(Courtesy The McFerrin Collection)

First photograph of the little elephant and the Egg. Courtesy Associated Press.

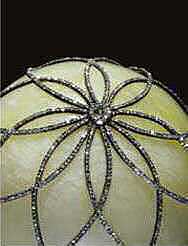

The Diamond Trellis Egg is made of gold, jadeite, rose-cut diamonds, silver and satin. The now missing miniature elephant was made of ivory, gold, rose-cut diamonds, enamel, ant brilliant diamonds.

Carved from pale green jadeite (also called bowenite), this Egg is enclosed in a lattice of rose-cut diamonds with gold mounts. Originally this Egg had a base representing three cherubs holding the Egg. The three cherubs were said to represent the three sons of the Imperial couple, the Grand Dukes Nicholas, George and Michael.

The Diamond Trellis Egg and its base with the three cherubs on an old photograph.

The original fitted case can be seen at the right. Photo courtesy "Laurent".

Background information

The miniature elephant was the first Fabergé automaton produced in his workshops, and was to be repeated eight years later in the 1900 Pine Cone Egg made for Barbara Kelch. Only six eggs are known to contain such an independent automaton, these are this 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg, the 1906 Swan Egg, the 1908 Peacock Egg, the 1911 Bay Tree Egg, the 1914 Catherine the Great Egg and the 1900 Kelch Pine Cone Egg.

The theme "elephant" is used several times by Fabergé in the Imperial Easter Egg. The elephant appears on the coat of arms of the Danish Royal family, and Maria was before her marriage to Alexander III, the Danish Princess Dagmar. The Diamond Trellis Egg is lined with white satin and has a space for the elephant and a key for winding it.

In the 1920's probably sold by officials of the Antikvariat to Michel Norman of a Paris-based Australian Company. Sold to Wartski, London. 1929 bought by a Mr. Kitson, UK. 1960 sold by Sotheby's London to a buyer's agent. 1962-1977 Private Collection UK, 1983 Private Collection, UK, London. 2012 McFerrin Collection, Houston USA.

---

Update October 2015: It was announced that the surprise to the 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg was found living in the Royal Collection in London. Curator of the Royal Collection, Caroline de Guitaut, announced the news at the St. Petersberg, Russia, Fabergé Museum.

Appearently the Fabergé marks on the small elephant were only recently discovered and the connecting link to the missing elephant surprise was made. Details and images of the find in the curator's talk which you can see here. For now only with Russian voice over! The discussion about the Diamond Trellis Egg starts at 52.07 miniutes of the video presentation!

Description elephant, from the Royal Collection webpage:

This automaton was made as the 'surprise' for the Diamond Trellis Egg, made by Carl Fabergé for Tsar Alexander III. The Tsar presented the egg to his wife Tsarina Marie Feodorovna for Easter 1892. The egg originally had a silver stand (now missing) and was fitted with a lining to hold an ivory elephant automaton and key. This automaton is described in Fabergé's original invoice and in an inventory of Imperial Easter Eggs made by Fabergé in the collection of Marie Feodorovna. The automaton is almost identical to the badge of the Danish Order of the Elephant, the most senior order of chivalry in Denmark, except that it is made of ivory rather than white enamel and that it incorporates a mechanism. The elephant is wound with a watch key through a hole hidden underneath the diamond cross on one side of the elephant. It walks on ratcheted wheels and lifts its head up and down.

Material: Ivory, gold, diamond, brass, nickel

Presented to Tsarina Marie Feodorovna by Tsar Alexander III of Russia, Easter 1892; sold by the Soviet Government through the Antikvariat late 1920s; with the dealer Wartski c. 1927-9. Acquired by King George V, 1935.

Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2015

To see how small and delicate the elephant is and to see the automaton in motion, see this little movie on Vimeo! Courtesy my friend Juan!

Update October 19: Russia Beyond the Headlines article about the discovery of the elephant.

Update October 20: Fabergé Museum online article about the discovery of the elephant.

---

The article and images below courtesy the Fabergé Research Site. Article first published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2015.

Identifying Materials Used by Fabergé - By Tim Adams and Carol Aiken

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection, Houston, Texas)

The correct identification of materials in Fabergé pieces is not always an easy task. Historical information is not at all times absolute or accurate, and descriptions are very often based on assumptions, incomplete information, or conscious embellishment. A question about gem and mineral identifications of Fabergé objects recently came up in conversations about the shell of the Diamond Trellis Egg in the McFerrin Collection, specifically whether it is jadeite or bowenite. One way of testing the material is by spectroscopic analysis, which determines the chemical or physical constitution of the stone. But this type of testing is rarely done, even to the highest profile Fabergé objects.

Art conservator Carol Aiken observed:

“Unfortunately, specialist gemologists or mineralogists are rarely consulted to identify or confirm most of the descriptions found in publications. For this reason, one generally should assume materials lists are at best descriptive and not absolutely accurate, unless evidence (specific type of analysis used, when and where it was done, proof of certification) has been provided to the contrary.”

She continued:

“The identification of metals can be as tricky as the gemstones. Some gold surfaces are plated and gold is generally alloyed with other metals. To be absolutely correct, making distinctions between vermeil (gold-plated silver) and ormolu (gold-plated bronze) is important, as is the recognition of the different colors of gold found in specific objects.”

Mineralogist James D. Dana in 1850 named bowenite after George T. Bowen (1803-1828), a chemist and mineralogist teaching at the University of Nashville, Tennessee. Bowen first discovered this member of the serpentine mineral family in Rhode Island, where it is now the state mineral. It can be identified not only spectroscopically, but can be differentiated from the two types of true jade, nephrite and jadeite, by measuring its specific gravity - bowenite is 2.6, nephrite 3.0, and jadeite 3.3.

Archival records, such as invoices, sales logs, or personal letters, would seem to be a reliable source for information on what stones or metal were used in creating a Fabergé object, but they can be misleading. Mistakes creep in when sales log entries are made in haste, or just the color of a stone is recorded, or some materials are left out completely. And in the case of bowenite, Fabergé did not use the term in his invoices, but generally referred to stones from the serpentine family as jadeite, which it very much resembles, so much so that the materials were often used interchangeably. In answer to the question initiating this discussion, the shell of the Diamond Trellis Egg is identified by the Houston Museum of Natural Science as bowenite.

Another common issue in the Fabergé invoices is a liberal use of the term “topaz” to refer to stones in the quartz family. Perhaps it was seen as a more elegant and marketable term, so “smoky quartz” became “smoky topaz”, and “citrine quartz” became “golden topaz”, etc. Of course, product enhancement has been a common practice in the advertising world for centuries, but it can be a source of confusion, too. As long as one understands these anomalies of fact exist, one can approach material identification more objectively.

Carol Aiken’s publications relating to this topic include:

“Imperial Easter Eggs: A Technical Study” in von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato, editors, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 76-83.

“The Many Golds of Fabergé” in Gilded Metals: History, Technology and Conservation, Terry Drayman-Weisser, editor, 2000, 297-306.

“Mrs. Pratt's Imperial Easter Eggs” in von Habsburg, Géza, et al., Fabergé Revealed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2011, 88-101.

![]()

See the elephant surprise on YouTube

March 7, 2017. The reunion between the little elephant and the Egg has taken place.

---> An exclusive loan arrangement between the Royal Collection of Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II and the Houston Museum of Natural Science will be the centerpiece of the new Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Gallery housed in the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals when it opens April 10th, 2017. Read this and more in this article!

![]() 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle

1900 Paris Exposition Universelle

![]() 1902 Von Dervis Fabergé Exhibition in Saint Petersburg, Russia

1902 Von Dervis Fabergé Exhibition in Saint Petersburg, Russia

page updated: January 9, 2019